PF (Packet Filter) is one of the most elegant firewall systems available on any operating system. Originally developed for OpenBSD and ported to FreeBSD, it combines a clean configuration syntax with powerful capabilities for filtering, NAT, traffic shaping, and logging. After running PF across multiple FreeBSD servers for years, I’ve developed a consistent configuration pattern that balances security with practicality.

This guide covers everything from basic concepts to production configurations, with tips and patterns I’ve refined through real-world deployment. Whether you’re protecting a single server or a complex jail infrastructure, the principles here should give you a solid foundation.

Core Concepts

PF processes rules in order, but with an important twist: the last matching rule wins (unless you use quick). This means you typically structure rules from general to specific, with explicit blocks at the top and specific allows below. The quick keyword short-circuits evaluation - when a quick rule matches, processing stops immediately.

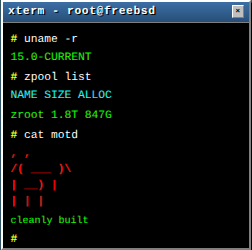

The configuration file lives at /etc/pf.conf. After editing, validate syntax with:

pfctl -nf /etc/pf.conf

If validation passes, load the rules:

pfctl -f /etc/pf.conf

To enable PF at boot, add to /etc/rc.conf:

pf_enable="YES"

pflog_enable="YES"

Since this guide covers NAT and routing traffic between jails and the internet, you must also enable packet forwarding. Without this, the firewall rules will load but traffic will die at the interface:

gateway_enable="YES"

ipv6_gateway_enable="YES"

Anatomy of a PF Configuration

A well-organized pf.conf follows a predictable structure. Here’s the skeleton I use across all servers:

# --- Macros ---

# Named variables for interfaces and addresses

# --- Tables ---

# Dynamic lists of addresses

# --- Options ---

# Global behavior settings

# --- Scrub ---

# Packet normalization

# --- NAT ---

# Network address translation

# --- RDR ---

# Port redirections

# --- Filtering ---

# The actual firewall rules

Each section has a distinct purpose. Let’s walk through them with practical examples.

Macros: Naming Your Network

Macros make configurations readable and maintainable. Define them at the top:

# --- Macros ---

ext_if = "vtnet0"

# "bastille0" is the bridge interface created by the Bastille framework.

# If using iocage or raw jails, this might be "lo1" or "bridge0".

int_if = "bastille0"

jail_net = "10.100.0.0/24"

jail_net6 = "2001:db8:1000:8000::/65"

# For IPv6 NAT (if needed), use a single address, not a CIDR block

host_ipv6 = "2001:db8:1000::1"

web_jail_v4 = "10.100.0.10"

web_jail_v6 = "2001:db8:1000:8000::10"

db_jail_v4 = "10.100.0.20"

# Lists use braces

trusted_ipv4 = "{ 198.51.100.22, 203.0.113.50 }"

trusted_ipv6 = "{ 2001:db8:ffff::/48 }"

Using macros means changing an IP address requires editing one line, not hunting through the entire ruleset. The $macro syntax references them in rules.

Tables: Dynamic Address Lists

Tables are PF’s mechanism for large or changing address sets. Unlike macros, tables can be modified at runtime without reloading the entire ruleset:

# --- Tables ---

table <bruteforce> persist

table <jails_v4> { $jail_net }

table <jails_v6> { $jail_net6 }

table <trusted_v4> persist { $trusted_ipv4 }

table <trusted_v6> persist { $trusted_ipv6 }

The persist keyword keeps the table in memory even when empty. This is essential for tables populated dynamically (like <bruteforce>).

Manage tables at runtime:

# Show table contents

pfctl -t bruteforce -T show

# Add an address

pfctl -t bruteforce -T add 192.0.2.100

# Remove an address

pfctl -t bruteforce -T delete 192.0.2.100

# Flush entire table

pfctl -t bruteforce -T flush

# Load from file

pfctl -t trusted_v4 -T add -f /etc/pf.trusted.txt

Tables scale efficiently - PF uses radix trees internally, so even tables with hundreds of thousands of entries (like GeoIP databases) perform well.

Options: Global Behavior

The options section configures PF’s global behavior:

# --- Options ---

set skip on lo0

set block-policy drop

set loginterface $ext_if

Key options explained:

set skip on lo0: Never filter loopback traffic. Critical for local services.set block-policy drop: Silently drop blocked packets (vs.returnwhich sends RST/ICMP). Drop is better for security - it gives attackers no information.set loginterface: Enable per-interface packet/byte counters. View withpfctl -si.

For large tables (GeoIP filtering, for example), increase the table entry limit:

set limit table-entries 1000000

Scrub: Packet Normalization

Scrubbing normalizes packets to prevent various attacks and fix fragmentation issues:

# --- Scrub ---

scrub in all fragment reassemble

scrub out all random-id max-mss 1500

The fragment reassemble directive reassembles fragmented packets before filtering - essential because fragments can be used to evade stateless filters. The random-id directive randomizes IP IDs on outbound packets, making traffic analysis harder. The max-mss clamps TCP MSS to prevent fragmentation issues, particularly important for tunneled traffic or VPN scenarios.

For specific interfaces with lower MTUs (tunnels, VSwitch connections), add targeted scrub rules:

scrub out on gif0 max-mss 1240

scrub out on $int_if max-mss 1410

NAT: Address Translation

NAT translates private addresses to public ones for outbound traffic. With FreeBSD jails on private networks, NAT is essential for IPv4:

# --- NAT ---

nat on $ext_if inet from <jails_v4> to any -> ($ext_if)

The parentheses around ($ext_if) make the NAT rule dynamic - if the external interface’s IP changes (DHCP), PF automatically uses the new address.

For IPv6, if you have a routed prefix, skip NAT entirely and route natively - this is the recommended approach. Jails get real global addresses and IPv6 works end-to-end as designed.

If you must NAT IPv6 (not recommended, but sometimes necessary), the syntax is similar. Ensure the target is a single address, not a CIDR block:

# host_ipv6 must be a single address assigned to the external interface

nat on $ext_if inet6 from <jails_v6> to any -> $host_ipv6

RDR: Port Forwarding

Redirections forward incoming traffic to internal hosts. For a web server jail:

# --- RDR ---

rdr pass on $ext_if inet proto tcp to ($ext_if) port {80, 443} -> $web_jail_v4

rdr pass on $ext_if inet6 proto tcp to $host_ipv6 port {80, 443} -> $web_jail_v6

The rdr pass syntax combines redirection with an implicit pass rule. Without pass, you’d need a separate filter rule for the translated traffic.

For port translation (external port differs from internal):

# External 2222 -> internal 22

rdr pass on $ext_if inet proto tcp from $trusted_runner to ($ext_if) port 2222 -> $deploy_jail port 22

Restricting the source in RDR rules is a powerful pattern - the service is invisible to everyone except specified sources.

Filtering: The Ruleset Core

The filtering section is where access control happens. Start with default deny:

# --- Filtering ---

# Block known bad actors immediately

block quick from <bruteforce>

# Default deny everything

block drop in log all

block drop out log all

# Allow all established connections out

pass out quick all keep state

# Anti-spoofing

antispoof quick for { $ext_if, bastille0 }

Understanding Quick and State

The quick keyword stops rule processing on match. Use it for definitive decisions:

# Immediately drop known attackers - no further processing

block quick from <bruteforce>

The keep state directive enables stateful filtering. When an outbound connection is allowed, PF creates a state entry that automatically permits return traffic. This is why a single pass out rule handles both the outbound packet and inbound replies.

Note: While newer OpenBSD versions of PF make keep state implicit, FreeBSD’s PF is based on an older codebase. Being explicit with keep state ensures connection tracking works exactly as intended across FreeBSD versions.

SSH Protection Pattern

Protecting SSH deserves special attention. This pattern restricts access to trusted sources, and automatically blocks brute-force attempts:

# SSH only from trusted sources

pass in quick on $ext_if proto tcp from <trusted_v4> to any port 22 \

flags S/SA keep state \

(max-src-conn 5, max-src-conn-rate 3/30, \

overload <bruteforce> flush global)

pass in quick on $ext_if inet6 proto tcp from <trusted_v6> to any port 22 \

flags S/SA keep state \

(max-src-conn 5, max-src-conn-rate 3/30, \

overload <bruteforce> flush global)

# Block and log all other SSH attempts (for monitoring)

block in log quick on $ext_if proto tcp from any to any port 22 label "ssh_blocked"

The state options deserve explanation:

max-src-conn 5: Maximum 5 simultaneous connections per source IPmax-src-conn-rate 3/30: Maximum 3 new connections per 30 seconds per sourceoverload <bruteforce>: Add violators to the bruteforce tableflush global: Kill all existing connections from the offender

The label on the block rule tags logged packets for easy filtering.

Essential ICMP

Never block all ICMP - it breaks essential network functionality:

# Essential ICMPv6 (required for IPv6 to function)

pass in quick inet6 proto ipv6-icmp icmp6-type { \

echoreq, echorep, neighbrsol, neighbradv, \

toobig, timex, paramprob }

# Useful ICMPv4

pass in inet proto icmp icmp-type { echoreq, unreach }

The IPv6 types are critical: - neighbrsol/neighbradv: Neighbor Discovery (IPv6’s ARP equivalent) - toobig: Path MTU Discovery (breaks connections if blocked) - echoreq/echorep: Ping (useful for diagnostics)

Jail Egress Rules

Allow jails to reach the internet while preventing them from directly accessing other internal networks:

# Jails can reach anywhere except internal networks

pass in quick on bastille0 from <jails_v4> to ! 10.100.0.0/24 keep state

pass in quick on bastille0 inet6 from <jails_v6> to ! 2001:db8:1000:8000::/65 keep state

The ! negation ensures jails can reach the internet but can’t directly contact other jails (unless explicitly permitted elsewhere).

Inter-Jail Communication

When jails need to communicate (database connections, for example), add explicit rules:

# Web jail -> Database jail (PostgreSQL + Redis)

pass in quick on bastille0 proto tcp from $web_jail_v4 to $db_jail_v4 port { 5432, 6379 } keep state

This explicit allowlisting is preferable to permitting all inter-jail traffic - it documents and enforces your service architecture.

Complete Example Configuration

Here’s a production-ready configuration for a server running multiple jails:

# --- Macros ---

ext_if = "vtnet0"

# Jail bridge interface (bastille0 for Bastille, bridge0 or lo1 for others)

int_if = "bastille0"

jail_net = "10.100.0.0/24"

jail_net6 = "2001:db8:1000:8000::/65"

host_ipv6 = "2001:db8:1000::1"

web_v4 = "10.100.0.10"

web_v6 = "2001:db8:1000:8000::10"

db_v4 = "10.100.0.20"

deploy_v4 = "10.100.0.25"

trusted_ipv4 = "{ 198.51.100.22, 203.0.113.50 }"

trusted_ipv6 = "{ 2001:db8:ffff::/48 }"

deploy_runner = "192.0.2.100"

# --- Tables ---

table <bruteforce> persist

table <jails_v4> { $jail_net }

table <jails_v6> { $jail_net6 }

table <trusted_v4> persist { $trusted_ipv4 }

table <trusted_v6> persist { $trusted_ipv6 }

# --- Options ---

set skip on lo0

set block-policy drop

set loginterface $ext_if

# --- Scrub ---

scrub in all fragment reassemble

scrub out all random-id max-mss 1500

# --- NAT ---

nat on $ext_if inet from <jails_v4> to any -> ($ext_if)

# --- RDR ---

rdr pass on $ext_if inet proto tcp to ($ext_if) port {80, 443} -> $web_v4

rdr pass on $ext_if inet6 proto tcp to $host_ipv6 port {80, 443} -> $web_v6

# Deployment SSH from CI runner only

rdr pass on $ext_if inet proto tcp from $deploy_runner to ($ext_if) port 2222 -> $deploy_v4 port 22

# --- Filtering ---

block quick from <bruteforce>

block drop in log all

block drop out log all

pass out quick all keep state

antispoof quick for { $ext_if, bastille0 }

# Management SSH

pass in quick on $ext_if proto tcp from <trusted_v4> to any port 22 \

flags S/SA keep state \

(max-src-conn 5, max-src-conn-rate 3/30, \

overload <bruteforce> flush global)

pass in quick on $ext_if inet6 proto tcp from <trusted_v6> to any port 22 \

flags S/SA keep state \

(max-src-conn 5, max-src-conn-rate 3/30, \

overload <bruteforce> flush global)

block in log quick on $ext_if proto tcp from any to any port 22 label "ssh_blocked"

# Essential ICMP

pass in quick inet6 proto ipv6-icmp icmp6-type { \

echoreq, echorep, neighbrsol, neighbradv, toobig, timex, paramprob }

pass in inet proto icmp icmp-type { echoreq, unreach }

# Web jail public access

pass in quick on $ext_if inet proto tcp from any to $web_v4 port {80, 443} flags S/SA keep state

pass in quick on $ext_if inet6 proto tcp from any to $web_v6 port {80, 443} flags S/SA keep state

# Inter-jail: web -> database

pass in quick on bastille0 proto tcp from $web_v4 to $db_v4 port { 5432, 6379 } keep state

# Jail egress

pass in quick on bastille0 from <jails_v4> to ! 10.100.0.0/24 keep state

pass in quick on bastille0 inet6 from <jails_v6> to ! 2001:db8:1000:8000::/65 keep state

Tips and Tricks

Viewing Loaded Rules

# Show all rules with rule numbers

pfctl -sr

# Verbose output with statistics

pfctl -sr -v

# Show NAT rules

pfctl -sn

# Show state table

pfctl -ss

# Show interface statistics

pfctl -si

Logging and Debugging

PF logs to pflog0, viewable with tcpdump:

# Live log viewing

tcpdump -n -e -ttt -i pflog0

# Read saved log file

tcpdump -n -e -ttt -r /var/log/pflog

# Filter by label

tcpdump -n -e -ttt -i pflog0 'label ssh_blocked'

Enable pflog in rc.conf and optionally configure rotation in /etc/newsyslog.conf.

Clearing Brute-Force Entries

Sometimes legitimate users get caught in rate limiting:

# Show who's blocked

pfctl -t bruteforce -T show

# Unblock specific IP

pfctl -t bruteforce -T delete 198.51.100.50

# Flush all blocked IPs

pfctl -t bruteforce -T flush

Consider a cron job to expire old entries:

# Clear entries older than 24 hours

pfctl -t bruteforce -T expire 86400

Testing Changes Safely

Before applying potentially locking changes, use the classic sysadmin safety net:

# Validate syntax first

pfctl -nf /etc/pf.conf

# Apply with automatic rollback

# (If you get locked out, rules revert after timeout)

echo "pfctl -f /etc/pf.conf.backup" | at now + 5 minutes

pfctl -f /etc/pf.conf

# If everything works, cancel the at job

atq

atrm <job_number>

Note: The at command requires the atd daemon. On minimal installs, you may need to enable it first:

# In /etc/rc.conf

atd_enable="YES"

# Then start it

service atd start

Monitoring Specific Traffic

Add temporary rules with counters for debugging:

pass in log on $ext_if proto tcp to port 443 label "https_debug"

Then watch:

pfctl -sr -v | grep https_debug

Sidebar: authpf for Bastion Hosts

For bastion hosts or jump servers, authpf provides per-user firewall rules that activate upon SSH login. Instead of static rules, the firewall dynamically permits access based on who’s connected.

authpf works by loading a user-specific ruleset (from /etc/authpf/users/$USER/ or /etc/authpf/authpf.rules) when the user logs in via SSH. When they log out, the rules are removed. This creates a “knock first” security model where services are invisible until authenticated.

Basic setup:

-

Set the user’s shell to

/usr/sbin/authpf:bash pw usermod bastion_user -s /usr/sbin/authpf -

Create

/etc/authpf/authpf.ruleswith rules to load on login:pf pass in quick on $ext_if from $user_ip to $internal_net -

The macro

$user_ipis automatically set to the connecting client’s address.

This approach is powerful for restricting access to internal networks: users must SSH to the bastion first, then their IP gets temporary firewall access. When the SSH session ends, access is revoked. Combined with short-lived certificates or hardware tokens, authpf creates a robust zero-trust perimeter without VPN complexity.

For production deployments, consider authpf as an alternative to VPNs for administrative access - it’s simpler to audit, integrates with existing SSH infrastructure, and provides per-session access control.

Conclusion

PF rewards careful configuration with robust, maintainable security. The patterns here - default deny, explicit allowlists, brute-force protection, and clean macro organization - scale from single servers to complex multi-jail deployments.

The key principles worth remembering:

- Default deny with explicit allows: Never assume traffic is safe

- State tracking: Let PF manage connection state rather than permitting return traffic explicitly

- Tables for dynamic data: Use tables for address lists that change or grow large

- Log selectively: Log blocked traffic for analysis, but avoid logging high-volume allowed traffic

- Test before applying: Always validate syntax and have a rollback plan

PF’s syntax takes time to internalize, but once it clicks, writing firewall rules becomes almost intuitive. The investment pays dividends in security, clarity, and the confidence that comes from truly understanding what your firewall permits.

References

- PF - The OpenBSD Packet Filter (PF’s canonical documentation)

- FreeBSD Handbook: Firewalls

- FreeBSD pf.conf(5) man page

- authpf(8) man page

A good firewall is invisible when everything works and invaluable when something goes wrong. PF sits quietly in the kernel, inspecting every packet, blocking the noise, and letting through exactly what you’ve specified. It’s one of those tools that makes you appreciate the Unix philosophy: do one thing well, make it composable, keep it simple.